News & Views: How much will cuts to NSF funding affect the future of scholarly publishing?

How might planned cuts to funding of the US National Science Foundation affect scholarly output? In our last News & Views we analyzed how the headline cuts might apply to relevant activities. This month we examine how journals may be impacted and model some scenarios quantifying the impact on global scholarly output.

Background

The US National Science Foundation is an independent US federal agency that supports science and engineering across the US and its territories. In its 2024 financial year (FY)1, it spent around $9.4 billion, funding approximately 25% of all federally supported research conducted by US colleges and universities.

In July we looked at how reported funding cuts and NSF budget cuts proposed by the US Government might affect the NSF’s output of research papers. We found that in the near term the effects would be limited, as the cuts focus on NSF activites that produce low volumes of papers. However, cuts proposed over the coming year may have a more profound effect as they are deep and affect research activities.

We have also previously analyzed proposed cuts to funding of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). We noted how cuts to the world’s largest producer of biomedical research could have a profound effect on publication outputs.

So how do cuts to the NSF stack up?

The effects on journals

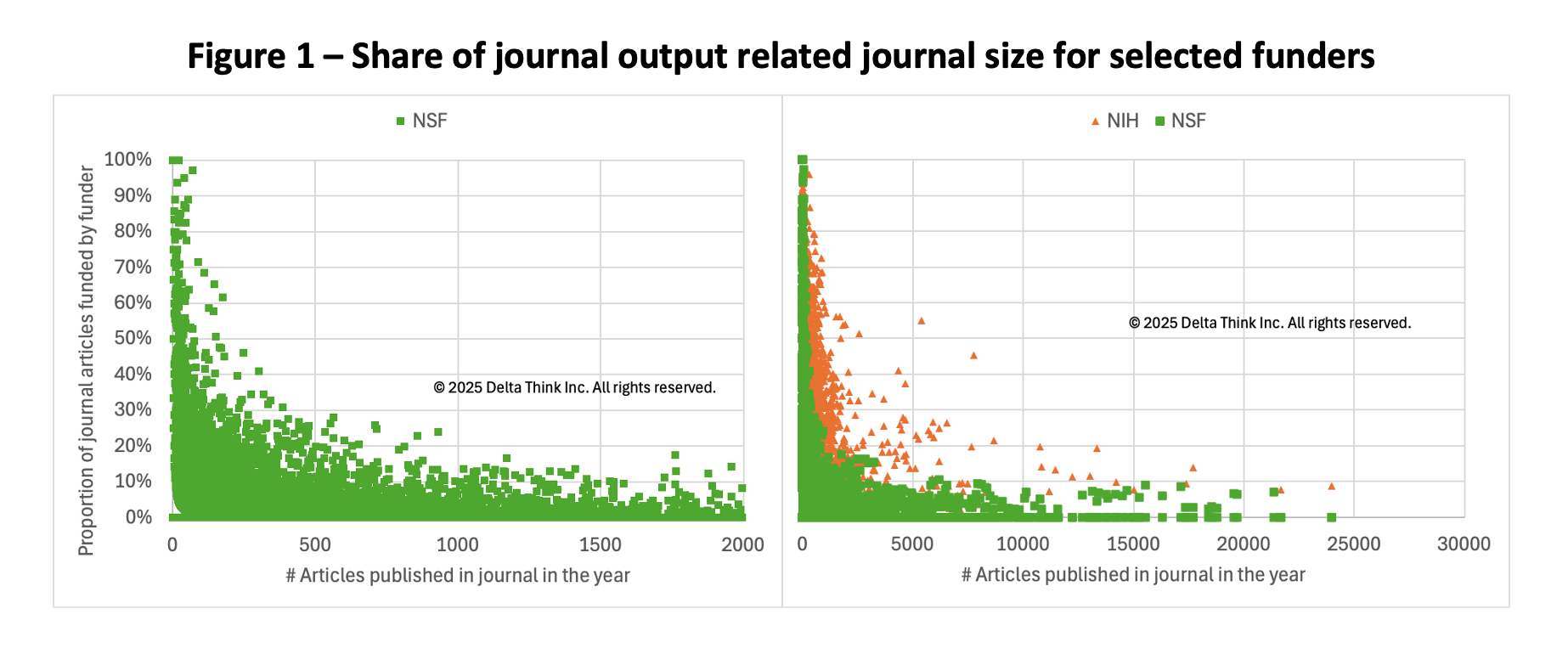

As ever, the headlines and averages are unevenly distributed, so we looked at how individual journals might be affected.

Sources: OpenAlex, Research Organization Registry (ROR), NSF, Delta Think analysis.

The charts above show the impact of funding on individual journals. They show the share of journal output attributable to some key funders, relating it to overall size of the journal. Each point represents one journal. The vertical axis shows the share of journal output attributable to the funder. The horizontal axis shows the journal size measured in the number of papers. The point of the charts is to show the overall patterns, not to highlight details of specific journals.

The left-hand chart focuses on papers arising from NSF-funded research.

- On average, 10% of papers in journals are attributable to NSF-funded research.

- Where the NSF affects a larger share of papers, the journals tend to be small (top left of the chart).

- For larger journals, the NSF accounts for smaller shares of output (bottom right of the chart). Note: so we can better see the clustering of small- and mid-sized journals, the very largest journals are not shown.

- Very few journals are reliant almost exclusively on NSF-funded research (top left of the chart).

The right-hand chart puts the NSF figures in context. It compares the NSF-funded articles (green squares) with NIH-funded ones (orange triangles).

- To keep the data manageable, the chart shows only journals with more than 2% of their papers funded by the funders in question. We can therefore focus on journals that may have a significant proportion of papers affected.

- Overall, the shape of the NIH clustering is similar to the NSF, but the NIH points are hidden behind the NSF ones. So, broadly, larger journals have a lower dependence on papers from an individual funder compared with smaller ones.

- However, the NSF funds a larger share of some larger journals, as indicated by the thick horizontal line of green dots around the 10,000 / 9% part of the chart.

- The NIH accounts for a higher share of papers in smaller journals, as indicated by the vertical cluster of orange dots to the right of the green ones from 20% upwards.

- On average, the NIH funds roughly 20% of journal papers and the NSF funds 10%.

So, while very large journals have a relatively low share of their papers arising from NSF and NIH funding, many smaller ones are heavily reliant on papers from these two funders.

The effects on publication output

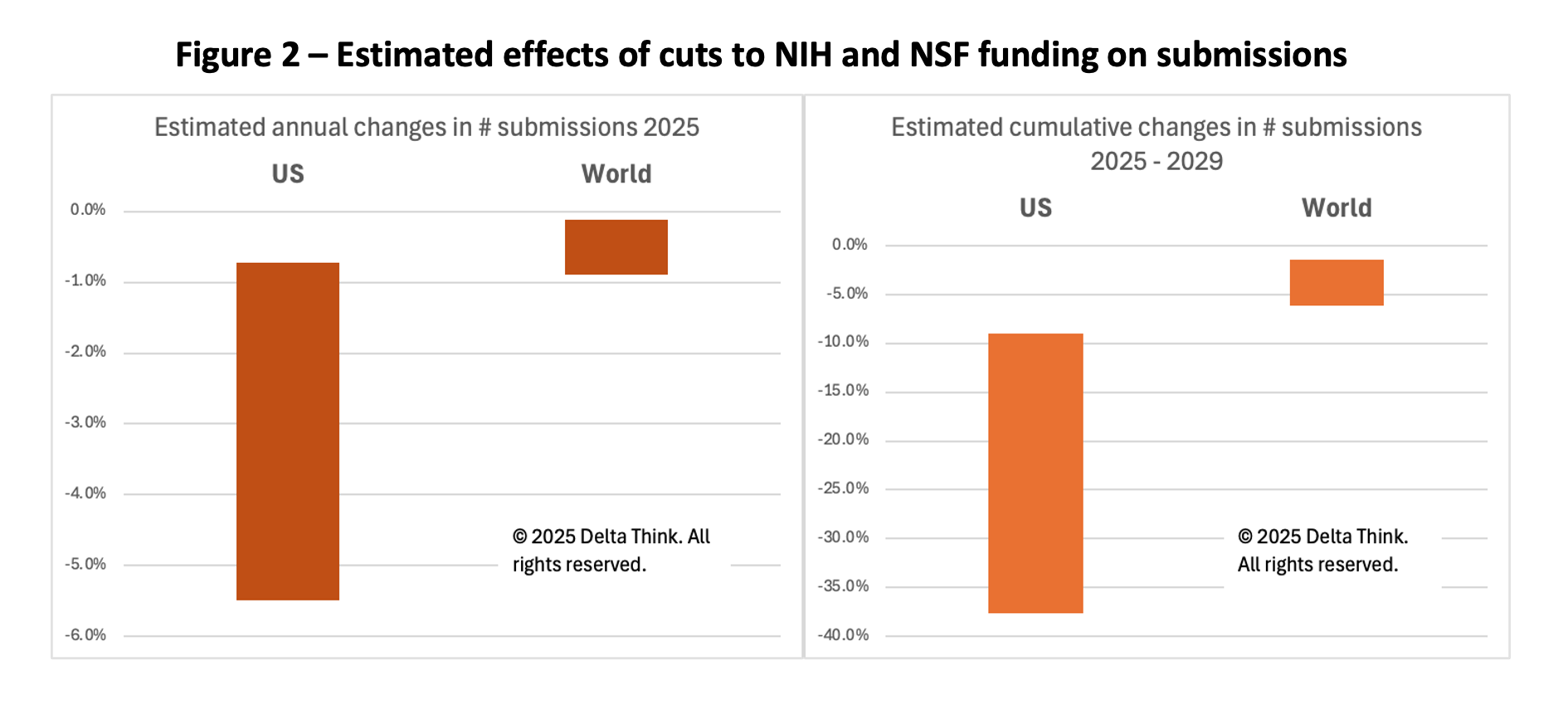

By taking a view on likely best- and worst-case scenarios and adding these to our previous analysis of the NIH, we estimate effects on scholarly output as follows.

Source: Delta Think analysis.

The charts above show ranges of drops in submissions. We projected funding cuts onto estimates of the share of output resulting from NIH and NSF funding. We then put this in the context of the total output from the US and globally. Given that projects have lead times before publication, we also needed to take a view on when cuts would work their way through to submissions.

- Each bar compares the estimated percentage reductions in submissions compared with numbers at the start of 2025. So, 0% means no change from a nominal steady state.

- The top of each bar shows the best case: Minimum cuts to numbers of grants or funding, excluding FY 2026 proposals.

- The bottom of each bar shows the worst case: Maximum cuts to grant funding, including FY 2026 proposals.

- The left-hand chart estimates effects of known cuts in 2025, pro-rated across the average grant length of 3.7 years for the NIH or 3 years for the NSF. The figures suggest a fall in submissions from the US of between 0.7% in 2025 (best case; top of leftmost bar) and 5.5% (worst case; bottom of leftmost bar). This would represent falls of between 0.1% and 0.9% in worldwide output (second-left bar).

- The right-hand chart shows the cumulative effects of cuts over the average grant timescale (taking us nominally to mid – late 2029). Here, we see much greater falls: The worst case sees US submissions falling by 38%, corresponding to a 6.2% drop in worldwide output.

- For the sake of analysis, we made assumptions about steady output of papers and that funding or grants (depending on the scenario) scale linearly with submissions. To compare like-for-like, we have assumed no other changes – such as to other areas of the world, to other US funding institutions, and no further cuts to NIH or NSF funding beyond those currently announced.

Conclusion

As we have previously noted, cuts to NIH funding have a profound effect on output because of the NIH’s sheer scale. Although smaller, the NSF is still a large funder, so how might cuts to it affect scholarly output?

In the near term, cuts to the NSF are unlikely to have much effect. This is because they largely focus on activities that don’t produce large volumes of papers (such as STEM education).

However, in the mid to longer term, the deep cuts to NSF funding directly affect its research activities and so add significant downward pressures on submissions – and by extension to publications. In the worst case scenarios, we previously estimated cuts to the NIH could lead to a 30% reduction in US output and a 5% reduction in global output. Add NSF cuts, and these effects rise to 38% and 6.2% respectively.

As before, we need to caveat that our analysis relies on assumptions – for example, that submissions scale linearly with funding and published papers scale linearly with submissions. These are reasonable, as rising submissions are cited as key drivers of scholarly output and revenue in the public financial reporting of major publishers.

Whatever the caveats, the effects of deep cuts to funding of large research institutions will inevitably have profound effects – particularly for those journals and publishers heavily reliant on those institutions’ supported research. Meanwhile, the larger publishers are in positions to weather things well. Direct US government funding only accounts for small proportion of their revenues, and government funding cycles have always come and gone over many years.

The future may already be here, but, as we are fond of saying, it remains unevenly distributed.

1 Financial years run October to September. E.g. the 2024 financial year ran from 1 October 2023 through 30 September 2024. This is the same as most US federal agencies, including the others we have analyzed (CDC, NIH, HHS).

---

This article is © 2025 Delta Think, Inc. It is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. Please do get in touch if you want to use it in other contexts – we’re usually pretty accommodating.

TOP HEADLINES

EIFL agreements increase publishing in open access – August 27, 2025

"Britt-Marie Wideberg, Manager of the EIFL Licensing Programme, analyzes the amount of research published in open access in 2024 by authors from EIFL partner countries to find out how EIFL-negotiated open access agreements are making a difference."

IReL Reaches Milestone of 10,000 Open Access Publications – August 20, 2025

"IReL has reached a major milestone in its commitment to open research and publishing transparency in enabling over 10,000 Irish research articles to be published open access, and in contributing data on them to OpenAPC."

eContent Pro International Press Debuts as First U.S.-Based Open Access-Only Book Publisher – August 5, 2025

"In a historic shift in the publishing industry, eContent Pro International Press has officially launched as the first U.S.-based book publisher to operate exclusively under a platinum open access publishing model."

SPARC – Intersection of Public Engagement and Open Access Presents Opportunities – July 30, 2025

"To solve many of the world’s most pressing problems, open access advocates believe knowledge needs to be shared widely. Those who support publicly engaged or community-engaged research emphasize the benefit of science being broadly accessible and informed by the contributions of multiple partners and/or interest holders to amplify impact..."

OA JOURNAL LAUNCHES

Royal Society sets out plan to move journals to full open access in 2026 through Subscribe to Open – August 6, 2025

"The Royal Society has agreed plans that would make its journals fully open access in 2026 by adopting the ‘Subscribe to Open’ model. Under plans agreed in July 2025, libraries subscribed to Royal Society journals will now be asked to support Subscribe to Open in 2026 through their subscriptions."

News & Views: Will cuts to National Science Foundation funding affect scholarly publishing activity?